Vitamin D

| Vitamin D | |

|---|---|

| Drug class | |

Cholecalciferol (D3) | |

| Class identifiers | |

| Synonyms | Calciferols |

| Use | Rickets, osteoporosis, osteomalacia, vitamin D deficiency |

| ATC code | A11CC |

| Biological target | vitamin D receptor |

| Clinical data | |

| Drugs.com | MedFacts Natural Products |

| External links | |

| MeSH | D014807 |

| Legal status | |

| In Wikidata | |

Vitamin D is a group of structurally related, fat-soluble compounds responsible for increasing intestinal absorption of calcium, magnesium, and phosphate, along with numerous other biological functions.[1][2] In humans, the most important compounds within this group are vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) and vitamin D2 (ergocalciferol).[2][3]

Unlike the other twelve vitamins, vitamin D is only conditionally essential - in a preindustrial society people had adequate exposure to sunlight and the vitamin was a hormone, as the primary natural source of vitamin D was the synthesis of cholecalciferol in the lower layers of the skin’s epidermis, triggered by a photochemical reaction with ultraviolet B (UVB) radiation from sunlight. Cholecalciferol and ergocalciferol can also be obtained through diet and dietary supplements. Foods such as the flesh of fatty fish are good natural sources of vitamin D; there are few other foods where it naturally appears in significant amounts.[2] In the U.S. and other countries, cow's milk and plant-based milk substitutes are fortified with vitamin D3, as are many breakfast cereals. Government dietary recommendations typically assume that all of a person's vitamin D is taken by mouth, given the potential for insufficient sunlight exposure due to urban living, cultural choices for amount of clothing worn when outdoors, and use of sunscreen because of concerns about safe levels of sunlight exposure, including risk of skin cancer.[2][4]: 362–394 The reality is that for most people, skin synthesis contributes more than diet sources.[5]

Cholecalciferol is converted in the liver to calcifediol (also known as calcidiol or 25-hydroxycholecalciferol), while ergocalciferol is converted to ercalcidiol (25-hydroxyergocalciferol). These two vitamin D metabolites, collectively referred to as 25-hydroxyvitamin D or 25(OH)D, are measured in serum to assess a person's vitamin D status. Calcifediol is further hydroxylated by the kidneys and certain immune cells to form calcitriol (1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol; 1,25(OH)2D), the biologically active form of vitamin D.[3] Calcitriol attaches to vitamin D receptors, which are nuclear receptors found in various tissues throughout the body.

The discovery of the vitamin in 1922 was due to effort to identify the dietary deficiency in children with rickets.[6][7] Adolf Windaus received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1928 for his work on the constitution of sterols and their connection with vitamins.”[8] Present day, government food fortification programs in some countries and recommendations to consume vitamin D supplements are intended to prevent or treat vitamin D deficiency rickets and osteomalacia. There are many other health conditions linked to vitamin D deficiency. However, the evidence for health benefits of vitamin D supplementation in individuals who are already vitamin D sufficient is unproven.[2][9][10][11]

Types

[edit]| Name | Chemical composition | Structure |

|---|---|---|

| Vitamin D1 | Mixture of molecular compounds of ergocalciferol with lumisterol, 1:1 | |

| Vitamin D2 | ergocalciferol (made from ergosterol) |

|

| Vitamin D3 | cholecalciferol

(made from 7-dehydrocholesterol in the skin). |

|

| Vitamin D4 | 22-dihydroergocalciferol |

|

| Vitamin D5 | sitocalciferol

(made from 7-dehydrositosterol) |

|

Several forms (vitamers) of vitamin D exist, with the two major forms being vitamin D2 or ergocalciferol, and vitamin D3 or cholecalciferol.[1] The common-use term "vitamin D" refers to both D2 and D3, which were chemically characterized, respectively, in 1931 and 1935. Vitamin D3 was shown to result from the ultraviolet irradiation of 7-dehydrocholesterol. Although a chemical nomenclature for vitamin D forms was recommended in 1981,[12] alternative names remain commonly used.[3]

Chemically, the various forms of vitamin D are secosteroids, meaning that one of the bonds in the steroid rings is broken.[13] The structural difference between vitamin D2 and vitamin D3 lies in the side chain: vitamin D2 has a double bond between carbons 22 and 23, and a methyl group on carbon 24. Vitamin D analogues have also been synthesized.[3]

Biology

[edit]

The active vitamin D metabolite, calcitriol, exerts its biological effects by binding to the vitamin D receptor (VDR), which is primarily located in the nuclei of target cells.[1][13] When calcitriol binds to the VDR, it enables the receptor to act as a transcription factor, modulating the gene expression of transport proteins involved in calcium absorption in the intestine, such as TRPV6 and calbindin.[15] The VDR is part of the nuclear receptor superfamily of steroid hormone receptors, which are hormone-dependent regulators of gene expression. These receptors are expressed in cells across most organs. VDR expression decreases with age.[1][5]

Activation of VDR in the intestine, bone, kidney, and parathyroid gland cells plays a crucial role in maintaining calcium and phosphorus levels in the blood, a process that is assisted by parathyroid hormone and calcitonin, thereby supporting bone health.[1][16][5] VDR also regulates cell proliferation and differentiation. Additionally, vitamin D influences the immune system, with VDRs being expressed in several white blood cells, including monocytes and activated T and B cells.[17]

Deficiency

[edit]Worldwide, more than one billion people[18] - infants, children, adults and elderly[19] - can be considered vitamin D deficient, with reported percentages dependent on what measurement is used to define "deficient."[20] Deficiency is common in the Middle-East,[19] Asia,[21] Africa[22] and South America,[23] but also exists in North America and Europe.[24][19][25][26] Ethnic, dark-skinned immigrant populations in North America, Europe and Australia have a higher percentage of deficiency compared to light-skinned populations that had their origins in Europe.[27][28][29]

Serum 25(OH)D concentration is used as a biomarker for vitamin D deficiency. Units of measurement are either ng/mL or nmol/L, with one ng/mL equal to 2.5 nmol/L. There is not a consensus on defining vitamin D deficiency, insufficiency, sufficiency, or optimal for all aspects of health.[20] According to the US Institute of Medicine Dietary Reference Intake Committee, below 30 nmol/L significantly increases the risk of vitamin D deficiency caused rickets in infants and young children, and reduces absorption of dietary calcium from the normal range of 60–80% to as low as 15%, whereas above 40 nmol/L is needed to prevent osteomalacia bone loss in the elderly, and above 50 nmol/L to be sufficient for all health needs.[4]: 75–111 Other sources have defined deficiency as less than 25 nmol/L, insufficiency as 30–50 nmol/L[30] and optimal as greater than 75 nmol/L.[31][32] Part of the controversy is because studies have reported differences in serum levels of 25(OH)D between ethnic groups, with studies pointing to genetic as well as environmental reasons behind these variations. African-American populations have lower serum 25(OH)D than their age-matched white population, but at all ages have superior calcium absorption efficiency, a higher bone mineral density and as elderly, a lower risk of osteoporosis and fractures.[4]: 439–440 Supplementation in this population to achieve proposed 'standard' concentrations could in theory cause harmful vascular calcification.[33]

Using the 25(OH)D assay as a screening tool of the generally healthy population to identify and treat individuals is considered not as cost-effective as a government mandated fortification program. Instead, there is a recommendation that testing should be limited to those showing symptoms of vitamin D deficiency or who have health conditions known to cause vitamin deficiency.[5][26]

Causes of insufficient vitamin D synthesis in the skin include insufficient exposure to UVB light from sunlight due to living in high latitudes (farther distance from the equator with resultant shorter daylight hours in winter). Serum concentration by the end of winter can be lower by one-third to half that at the end of summer.[4]: 100–101, 371–379 [5][34] Other causes of insufficient synthesis are sunlight being blocked by air pollution,[35] urban/indoor living, long-term hospitalizations and stays in extended care facilities, cultural or religious lifestyle choices that favor sun-blocking clothing, recommendations to use sun-blocking clothing or sunscreen to reduce risk of skin cancer, and lastly, the UV-B blocking nature of dark skin.[25]

Consumption of foods that naturally contain vitamin D are rarely sufficient to maintain recommended serum concentration of 25(OH)D in the absence of the contribution of skin synthesis. Fractional contributions are roughly 20% diet and 80% sunlight.[5] Vegans had lower dietary intake of vitamin D and lower serum 25(OH)D when compared to omnivores, with lacto-ovo-vegetarians falling in between due to the vitamin content of egg yolks and fortified dairy products.[36] Governments have mandated or voluntary food fortification programs to bridge the difference in, respectively, 15 and 10 countries.[37] The United States is one of the few mandated countries. The original fortification practices, circa early 1930s, were limited to cow's milk, which had a large effect on reducing infant and child rickets. In July 2016 the US Food and Drug Administration approved the addition of vitamin D to plant milk beverages intended as milk alternatives, such as beverages made from soy, almond, coconut and oats.[38] At an individual level, people may choose to consume a multi-vitamin/mineral product or else a vitamin-D-only product.[39]

There are many disease states, medical treatments and medications that put people at risk for vitamin D deficiency. Chronic diseases that increase risk include kidney and liver failure, Crohn’s disease, inflammatory bowel disease and malabsorption syndromes such as cystic fibrosis, and hyper- or hypo-parathyroidism.[25] Obesity sequesters vitamin D in fat tissues thereby lowering serum levels,[40] but bariatric surgery to treat obesity interferes with dietary vitamin D absorption, also causing deficiency.[41] Medications include antiretrovirals, anti-seizure drugs, glucocorticoids, systemic antifungals such as ketoconazole, cholestyramine and rifampicin.[5][25] Organ transplant recipients receive immunosuppressive therapy that is associated with an increased risk to develop skin cancer, so they are advised to avoid sunlight exposure, and to take a vitamin D supplement.[42]

Treatment

[edit]Daily dose regimens are preferred to admission of large doses at weekly or monthly schedules, and D3 may be preferred over D2, but there is a lack of consensus as to optimal type, dose, duration or what to measure to deem success. Daily regimens on the order of 4,000 IU/day (for other than infants) have a greater effect on 25(OH)D recovery from deficiency and lower risk of side effects compared to weekly or monthly bolus doses, with the latter as high as 100,000 IU. The only advantage for bolus dosing could be better compliance, as bolus dosing is usually administered by a healthcare professional rather than self-administered.[5] While some studies have found that vitamin D3 raises 25(OH)D blood levels faster and remains active in the body longer,[43][44] others contend that vitamin D2 sources are equally bioavailable and effective for raising and sustaining 25(OH)D.[45][46] If digestive disorders compromise absorption, then intramuscular injection of up to 100,000 IU of vitamin D3 is therapeutic.[5]

Dark skin as deficiency risk

[edit]Melanin, specifically the sub-type eumelanin, is a biomolecule consisting of linked molecules of oxidized amino acid tyrosine. It is produced by cells called melanocytes in a process called melanogenesis. In skin, melanin is located in the bottom layer (the stratum basale) of the skin's epidermis. Melanin can be permanently incorporated into skin, resulting in dark skin, or else have its synthesis initiated by exposure to UV radiation, causing the skin to darken as a temporary sun tan. Eumelanin is an effective absorbent of light; the pigment is able to dissipate over 99.9% of absorbed UV radiation.[47] Because of this property, eumelanin is thought to protect skin cells from sunlight's Ultraviolet A (UVA) and Ultraviolet B (UVB) radiation damage, reducing the risk of skin tissue folate depletion, preventing premature skin aging and reducing the risks of sunburn and skin cancer.[48] Melanin inhibits UVB-powered vitamin D synthesis in the skin. In areas of the world not distant from the equator, abundant, year-round exposure to sunlight means that even dark-skinned populations have adequate skin synthesis.[49] However, when dark-skinned people cover much of their bodies with clothing for cultural or climate reasons, or are living a primarily indoor life in urban conditions, or live at higher latitudes which provide less sunlight in winter, they are at risk for vitamin D deficiency.[25][50] The last cause has been described as a "latitude-skin color mismatch."[49]

To use one country as an example, in the United States, vitamin D deficiency is particularly common among non-white Hispanic and African-American populations.[30][49][51] However, despite having on-average 25(OH)D serum contentrations below the 50 nmol/L amount considered sufficient, African Americans have higher bone mineral density and lower fracture risk when compared to European-origin people. Possible mechanisms may include higher calcium retention, lower calcium excretion and greater bone resistance to parathyroid hormone,[49][51][52] also genetically lower serum vitamin D-binding protein which would result in adequate bioavailable 25(OH)D despite total serum 25(OH)D being lower.[53] The bone density and fracture risk paradox does not necessarily carry over to non-skeletal health conditions such as arterial calcification, cancer, diabetes or all-cause mortality. There is conflicting evidence that in the African American population, 'deficiency' as currently defined increases the risk of non-skeletal health conditions, and some evidence that supplementation increases risk,[49][51] including for harmful vascular calcification.[33] African Americans, and by extension other dark-skinned populations, may need different definitions for vitamin D deficiency, insufficiency and adequate.[33]

Infant deficiency

[edit]Comparative studies carried out in lactating mothers indicate a mean value of vitamin D content in breast milk of 45 IU/liter.[54] This vitamin D content is clearly too low to meet the vitamin D requirement of 400 IU/day recommended by several government organizations (...as breast milk is not a meaningful source of vitamin D."[4]: 385 ). The same government organizations recommend that lactating women consume 600 IU/day,[2][55][56][57] but this is insufficient to raise breast milk content to deliver recommended intake.[54] There is evidence that breast milk content can be increased, but because the transfer of the vitamin from the lactating mother's serum to milk is inefficient, this requires that she consume a dietary supplement in excess of the government-set safe upper limit of 4,000 IU/day.[54] Given the shortfall, there are recommendations that breast-fed infants be fed a vitamin D dietary supplement of 400 IU/day during the first year of life.[54] If not breast feeding, infant formulas are designed to deliver 400 IU/day for an infant consuming a liter of formula per day[58] - a normal volume for a full-term infant after first month.[59]

Excess

[edit]Vitamin D toxicity, or hypervitaminosis D, is the toxic state of an excess of vitamin D. It is rare, having occurred historically during a time of unregulated fortification of foods, especially those provided to infants,[4]: 431–432 or in more recently, with consumption of high-dose vitamin D dietary supplements following inappropriate prescribing, non-prescribed consumption of high-dose, over-the-counter preparations, or manufacturing errors resulting in content far in excess of what is on the label.[39][60][61] Ultraviolet light alone - sunlight or tanning beds - can raise serum 25(OH)D concentration to higher than 100 nmol/L, but not to a level that causes hypervitaminosis D.[62]

There is no general agreement about the intake levels at which vitamin D may cause harm. From the IOM review, "Doses below 10,000 IU/day are not usually associated with toxicity, whereas doses equal to or above 50,000 IU/day for several weeks or months are frequently associated with toxic side effects including documented hypercalcemia."[4]: 427 The normal range for blood concentration of 25-hydroxyvitamin D in adults is 20 to 50 nanograms per milliliter (ng/mL; equivalant to 50 to 125 nmol/L). Blood levels necessary to cause adverse effects in adults are thought to be greater than about 150 ng/mL.[4]: 424–446 An excess of vitamin D causes abnormally hypercalcaemia (high blood concentrations of calcium), which can cause overcalcification of the bones and soft tissues including arteries, heart, and kidneys. Untreated, this can lead to irreversible kidney failure. Symptoms of vitamin D toxicity may include the following: increased thirst, increased urination, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, decreased appetite, irritability, constipation, fatigue, muscle weakness, and insomnia. In almost every case, stopping the vitamin D supplementation combined with a low-calcium diet and corticosteroid drugs will allow for a full recovery within a month.[63][64][65]

In 2011, the U.S. National Academy of Medicine revised tolerable upper intake levels (UL) to protect against vitamin D toxicity. Before the revision the UL for ages 9+ years was 50 μg/d (2000 IU/d).[4]: 424–445 Per the revision: "UL is defined as "the highest average daily intake of a nutrient that is likely to pose no risk of adverse health effects for nearly all persons in the general population."[66] The U.S. ULs in microgram (mcg or μg) and International Units (IU) for both males and females, by age, are:

- 0–6 months: 25 μg/d (1000 IU/d)

- 7–12 months: 38 μg/d (1500 IU/d)

- 1–3 years: 63 μg/d (2500 IU/d)

- 4–8 years: 75 μg/d (3000 IU/d)

- 9+ years: 100 μg/d (4000 IU/d)

- Pregnant and lactating: 100 μg/d (4000 IU/d)

As shown in the Dietary intake section, different government organizations have set different ULs for age groups, but there is accord on the adult maximum of 100 μg/d (4000 IU/d). In contrast, some non-government authors have proposed a safe upper intake level of 250 μg (10,000 IU) per day in healthy adults.[67][68] In part, this is based on the observation that endogenous skin production with full body exposure to sunlight or use of tanning beds is comparable to taking an oral dose between 250 μg and 625 μg (10,000 IU and 25,000 IU) per day and maintaining blood concentrations on the order of 100 ng/mL.[69]

Although in the U.S. the adult UL is set at 4,000 IU/day, over-the-counter products are available at 5,000, 10,000 and even 50,000 IU (the last with directions to take once a week). The percentage of the U.S. population taking over 4,000 IU/day has increased since 1999.[39]

Special cases

[edit]Idiopathic infantile hypercalcemia is caused by a mutation of the CYP24A1 gene, leading to a reduction in the degradation of vitamin D. Infants who have such a mutation have an increased sensitivity to vitamin D and in case of additional intake a risk of hypercalcaemia.[70] The disorder can continue into adulthood.[71]

Health effects

[edit]Supplementation with vitamin D is a reliable method for preventing or treating rickets. On the other hand, the effects of vitamin D supplementation on non-skeletal health are uncertain.[72][73] A review did not find any effect from supplementation on the rates of non-skeletal disease, other than a tentative decrease in mortality in the elderly.[74] Vitamin D supplements do not alter the outcomes for myocardial infarction, stroke or cerebrovascular disease, cancer, bone fractures or knee osteoarthritis.[10][75]

A US Institute of Medicine (IOM) report states: "Outcomes related to cancer, cardiovascular disease and hypertension, and diabetes and metabolic syndrome, falls and physical performance, immune functioning and autoimmune disorders, infections, neuropsychological functioning, and preeclampsia could not be linked reliably with intake of either calcium or vitamin D, and were often conflicting."[4]: 5 Evidence for and against each disease state is provided in detail.[4]: 124–299 Some researchers claim the IOM was too definitive in its recommendations and made a mathematical mistake when calculating the blood level of vitamin D associated with bone health.[76] Members of the IOM panel maintain that they used a "standard procedure for dietary recommendations" and that the report is solidly based on the data.[76]

Mortality, all-causes

[edit]Vitamin D3 supplementation has been tentatively found to lead to a reduced risk of death in the elderly,[77][74] but the effect has not been deemed pronounced, or certain enough, to make taking supplements recommendable.[10] Other forms (vitamin D2, alfacalcidol, and calcitriol) do not appear to have any beneficial effects concerning the risk of death.[77] High blood levels appear to be associated with a lower risk of death, but it is unclear if supplementation can result in this benefit.[78] Both an excess and a deficiency in vitamin D appear to cause abnormal functioning and premature aging.[79][80] The relationship between serum calcifediol concentrations and all-cause mortality is "U-shaped": mortality is elevated at high and low calcifediol levels, relative to moderate levels. Harm from elevated calcifediol appears to occur at a lower level in dark-skinned Canadian and United States populations than in the light-skinned populations.[4]: 424–435

Bone health

[edit]Rickets

[edit]

Rickets, a childhood disease, is characterized by impeded growth and soft, weak, deformed long bones that bend and bow under their weight as children start to walk. Maternal vitamin D deficiency can cause fetal bone defects from before birth and impairment of bone quality after birth.[81][82] Rickets typically appear between 3 and 18 months of age.[83] This condition can be caused by vitamin D, calcium or phosphorus deficiency.[84] Vitamin D deficiency remains the main cause of rickets among young infants in most countries because breast milk is low in vitamin D, and darker skin, social customs, and climatic conditions can contribute to inadequate sun exposure.[citation needed] A post-weaning Western omnivore diet characterized by high intakes of meat, fish, eggs and vitamin D fortified milk is protective, whereas low intakes of those foods and high cereal/grain intake contribute to risk.[85][86][87] For young children with rickets, supplementation with vitamin D plus calcium was superior to the vitamin alone for bone healing.[88][89]

Osteomalacia and osteoporosis

[edit]

Characteristics of osteomalacia are softening of the bones, leading to bending of the spine, bone fragility, and increased risk for fractures.[1] Osteomalacia is usually present when 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels are less than about 10 ng/mL.[91] Osteomalacia progress to osteoporosis, a condition of reduced bone mineral density with increased bone fragility and risk of bone fractures. Osteoporosis can be a long-term effect of calcium and/or vitamin D insufficiency, the latter contributing by reducing calcium absorption.[2] In the absence of confirmed vitamin D deficiency there is no evidence that vitamin D supplementation without concomitant calcium slows or stops the progression of osteomalacia to osteoporosis.[9] For older people with osteoporosis, taking vitamin D with calcium may help prevent hip fractures, but it also slightly increases the risk of stomach and kidney problems.[92][93] The reduced rick for fractures is not seen in healthier, community-dwelling elderly.[10][94][95] Low serum vitamin D levels have been associated with falls,[96] but taking extra vitamin D does not appear to reduce that risk.[97]

Athletes who are vitamin D deficient are at an increased risk of stress fractures and/or major breaks, particularly those engaging in contact sports. Incremental decreases in risk are observed with rising serum 25(OH)D concentrations plateauing at 50 ng/mL with no additional benefits seen in levels beyond this point.[98]

Cancer

[edit]While serum low 25-hydroxyvitamin D status has been associated with a higher risk of cancer in observational studies,[99][100][101] the general conclusion is that there is insufficient evidence for an effect of vitamin D supplementation on the risk of cancer,[2][102][103] although there is some evidence for reduction in cancer mortality.[99][104]

Cardiovascular disease

[edit]Vitamin D supplementation is not associated with a reduced risk of stroke, cerebrovascular disease, myocardial infarction, or ischemic heart disease.[10][105][106] Supplementation does not lower blood pressure in the general population.[107][108][109] One meta-analysis found a small increase in risk of stroke when calcium and vitamin D supplements were taken together.[110]

Immune system

[edit]Infectious diseases

[edit]In general, vitamin D functions to activate the innate and dampen the adaptive immune systems with antibacterial, antiviral and anti-inflammatory effects.[111][112] Low serum levels of vitamin D appear to be a risk factor for tuberculosis.[113] However, supplementation trials showed no benefit.[114][115] Vitamin D supplementation at low doses may slightly decrease the overall risk of acute respiratory tract infections.[116] The benefits were found in children and adolescents, and were not confirmed with higher doses.[116]

Inflammatory bowel disease

[edit]Vitamin D deficiency has been linked to the severity of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).[117] However, whether vitamin D deficiency causes IBD or is a consequence of the disease is not clear.[118] Supplementation leads to improvements in scores for clinical inflammatory bowel disease activity and biochemical markers and[119][118] less frequent relapse of symptoms in IBD.[118]

COVID-19

[edit]As of September 2022[update] the US National Institutes of Health state there is insufficient evidence to recommend for or against using vitamin D supplementation to prevent or treat COVID-19.[120] The UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) does not recommend to offer a vitamin D supplement to people solely to prevent or treat COVID-19.[121][122] Both organizations included recommendations to continue the previous established recommendations on vitamin D supplementation for other reasons, such as bone and muscle health, as applicable. Both organizations noted that more people may require supplementation due to lower amounts of sun exposure during the pandemic.[120][121]

Vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency have been associated with adverse outcomes in COVID-19.[123][124][125][126][127][128] A review of supplement trials indicated a lower intensive care unit (ICU) admission rate compared to those without supplementation, but without a change in mortality,[129] but another review considered the evidence for treatment of COVID-19 to be very uncertain.[130] Another meta-analysis stated that the use of high doses of vitamin D in people with COVID-19 is not based on solid evidence although calcifediol supplementation may have a protective effect on ICU admissions.[126]

Other conditions

[edit]Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

[edit]Vitamin D supplementation substantially reduced the rate of moderate or severe exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).[131]

Asthma

[edit]Vitamin D supplementation does not help prevent asthma attacks or alleviate symptoms.[132]

Diabetes

[edit]A meta-analysis reported that vitamin D supplementation significantly reduced the risk of type 2 diabetes for non-obese people with prediabetes.[133] Another meta-analysis reported that vitamin D supplementation significantly improved glycemic control [homeostatic model assessment-insulin resistance (HOMA-IR)], hemoglobin A1C (HbA1C), and fasting blood glucose (FBG) in individuals with type 2 diabetes.[134] In prospective studies, high versus low levels of vitamin D were respectively associated with a significant decrease in risk of type 2 diabetes, combined type 2 diabetes and prediabetes, and prediabetes.[135] A systematic review included one clinical trial that showed vitamin D supplementation together with insulin maintained levels of fasting C-peptide after 12 months better than insulin alone.[136]

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

[edit]A meta-analysis of observational studies showed that children with ADHD have lower vitamin D levels and that there was a small association between low vitamin D levels at the time of birth and later development of ADHD.[137] Several small, randomized controlled trials of vitamin D supplementation indicated improved ADHD symptoms such as impulsivity and hyperactivity.[138]

Depression

[edit]Clinical trials of vitamin D supplementation for depressive symptoms have generally been of low quality and show no overall effect, although subgroup analysis showed supplementation for participants with clinically significant depressive symptoms or depressive disorder had a moderate effect.[139]

Cognition and dementia

[edit]A systematic review of clinical studies found an association between low vitamin D levels with cognitive impairment and a higher risk of developing Alzheimer's disease. However, lower vitamin D concentrations are also associated with poor nutrition and spending less time outdoors. Therefore, alternative explanations for the increase in cognitive impairment exist and hence a direct causal relationship between vitamin D levels and cognition could not be established.[140]

Schizophrenia

[edit]People diagnosed with schizophrenia tend to have lower serum vitamin D concentrations compared to those without the condition. This may be a consequence of the disease rather than a cause, due, for example, to low dietary vitamin D and less time spent exposed to sunlight.[141][142] Results from supplementation trials have been inconclusive.[141]

Sexual dysfunction

[edit]Erectile dysfunction can be a consequence of vitamin D deficiency. Mechanisms may include regulation of vascular stiffness, the production of vasodilating nitric oxide, and the regulation of vessel permeability. However, the clinical trial literature does not yet contain sufficient evidence that supplementation treats the problem. Part of the complexity is that vitamin D deficiency is also linked to morbidities that are associated with erectile dysfunction, such as obesity, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hypercholesterolemia, chronic kidney disease and hypogonadism.[143][144]

In women, vitamin D receptors are expressed in the superficial layers of the urogenital organs. There is an association between vitamin D deficiency and a decline in sexual functions, including sexual desire, orgasm, and satisfaction in women, with symptom severity correlated with vitamin D serum concentration. The clinical trial literature does not yet contain sufficient evidence that supplementation reverses these dysfunctions or improves other aspects of vaginal or urogenital health.[145]

Pregnancy

[edit]Pregnant women often do not take the recommended amount of vitamin D.[146] Low levels of vitamin D in pregnancy are associated with gestational diabetes, pre-eclampsia, and small for gestational age infants.[147] Although taking vitamin D supplements during pregnancy raises blood levels of vitamin D in the mother at term, the full extent of benefits for the mother or baby is unclear.[147][148][149]

Obesity

[edit]Obesity increases the risk of having low serum vitamin D. Supplementation does not lead to weight loss, but weight loss increases serum vitamin D. The theory is that fatty tissue sequesters vitamin D.[40] Bariatric surgery as a treatment for obesity can lead to vitamin deficiencies. Long-term follow-up reported deficiencies for vitamins D, E, A, K and B12, with D the most common at 36%.[41]

Uterine fibroids

[edit]There is evidence that the pathogenesis of uterine fibroids is associated with low serum vitamin D and that supplementation reduces the size of fibroids.[150][151]

Allowed health claims

[edit]Governmental regulatory agencies stipulate for the food and dietary supplement industries certain health claims as allowable as statements on packaging.

Europe: European Food Safety Authority (EFSA)

- normal function of the immune system[152]

- normal inflammatory response[152]

- normal muscle function[152]

- reduced risk of falling in people over age 60[153]

US: Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

- "Adequate calcium and vitamin D, as part of a well-balanced diet, along with physical activity, may reduce the risk of osteoporosis."[90]

Canada: Health Canada

- "Adequate calcium and regular exercise may help to achieve strong bones in children and adolescents and may reduce the risk of osteoporosis in older adults. An adequate intake of vitamin D is also necessary."[154]

Japan: Foods with Nutrient Function Claims (FNFC)

- "Vitamin D is a nutrient which promotes the absorption of calcium in the gut intestine and aids in the development of bone."[155]

Dietary intake

[edit]| United Kingdom | ||

| Age group | Intake (μg/day) | Maximum intake (μg/day)[55] |

|---|---|---|

| Breast-fed infants 0–12 months | 8.5 – 10 | 25 |

| Formula-fed infants (<500 mL/d) | 10 | 25 |

| Children 1 – 10 years | 10 | 50 |

| Children >10 and adults | 10 | 100 |

| United States | ||

| Age group | RDA (IU/day)[4] | (μg/day) |

| Infants 0–6 months | 400* | 10 |

| Infants 6–12 months | 400* | 10 |

| 1–70 years | 600 | 15 |

| Adults > 70 years | 800 | 20 |

| Pregnant/Lactating | 600 | 15 |

| Age group | Tolerable upper intake level (IU/day)[4] | (μg/day) |

| Infants 0–6 months | 1,000 | 25 |

| Infants 6–12 months | 1,500 | 37.5 |

| 1–3 years | 2,500 | 62.5 |

| 4–8 years | 3,000 | 75 |

| 9+ years | 4,000 | 100 |

| Pregnant/lactating | 4,000 | 100 |

| Canada | ||

| Age group | RDA (IU)[56] | Tolerable upper intake (IU)[56] |

| Infants 0–6 months | 400* | 1,000 |

| Infants 7–12 months | 400* | 1,500 |

| Children 1–3 years | 600 | 2,500 |

| Children 4–8 years | 600 | 3,000 |

| Children and adults 9–70 years | 600 | 4,000 |

| Adults > 70 years | 800 | 4,000 |

| Pregnancy & lactation | 600 | 4,000 |

| Australia and New Zealand | ||

| Age group | Adequate Intake (μg)[156] | Upper Level of Intake (μg)[156] |

| Infants 0–12 months | 5* | 25 |

| Children 1–18 years | 5* | 80 |

| Adults 19–50 years | 5* | 80 |

| Adults 51–70 years | 10* | 80 |

| Adults > 70 years | 15* | 80 |

| European Food Safety Authority | ||

| Age group | Adequate Intake (μg)[57] | Tolerable upper limit (μg)[157] |

| Infants 0–12 months | 10 | 25 |

| Children 1–10 years | 15 | 50 |

| Children 11–17 years | 15 | 100 |

| Adults | 15 | 100 |

| Pregnancy & Lactation | 15 | 100 |

| * Adequate intake, no RDA/RDI yet established | ||

Recommended levels

[edit]Various government institutions have proposed different recommendations for the amount of daily intake of vitamin D. These vary according to age, pregnancy or lactation, and the extent assumptions are made regarding skin synthesis.[2][55][56][57][156] Older recommendations were lower. For example, the US Adequate Intake recommendations from 1997 were 200 IU/day for infants, children, adults to age 50 and women during pregnancy or lactation, 400 IU/day for ages 51-70 and 600 IU/day for 71 and older.[158]

Conversion: 1 μg (microgram) = 40 IU (international unit).[55] For dietary recommendation and food labeling purposes government agencies consider vitamin D3 and D2 bioequivalent.[4][55][56][57][156]

United Kingdom

[edit]The UK National Health Service (NHS) recommends that people at risk of vitamin D deficiency, breast-fed babies, formula-fed babies taking less than 500 ml/day, and children aged 6 months to 4 years, should take daily vitamin D supplements throughout the year to ensure sufficient intake.[55] This includes people with limited skin synthesis of vitamin D, who are not often outdoors, are frail, housebound, living in a care home, or usually wearing clothes that cover up most of the skin, or with dark skin, such as having an African, African-Caribbean or south Asian background. Other people may be able to make adequate vitamin D from sunlight exposure from April to September. The NHS and Public Health England recommend that everyone, including those who are pregnant and breastfeeding, consider taking a daily supplement containing 10 μg (400 IU) of vitamin D during autumn and winter because of inadequate sunlight for vitamin D synthesis.[159]

United States

[edit]The dietary reference intake for vitamin D issued in 2011 by the Institute of Medicine (IoM) (renamed National Academy of Medicine in 2015), superseded previous recommendations which were expressed in terms of adequate intake. The recommendations were formed assuming the individual has no skin synthesis of vitamin D because of inadequate sun exposure. The reference intake for vitamin D refers to total intake from food, beverages, and supplements, and assumes that calcium requirements are being met.[4]: 362–394 The tolerable upper intake level (UL) is defined as "the highest average daily intake of a nutrient that is likely to pose no risk of adverse health effects for nearly all persons in the general population."[4]: 424–446 Although ULs are believed to be safe, information on the long-term effects is incomplete and these levels of intake are not recommended for long-term consumption.[4]: 404 : 439–440

For US food and dietary supplement labeling purposes, the amount in a serving is expressed as a percent of Daily Value (%DV). For vitamin D labeling purposes, 100% of the daily value was 400 IU (10 μg), but in May 2016, it was revised to 800 IU (20 μg) to bring it into agreement with the recommended dietary allowance (RDA).[160][161] A table of the old and new adult daily values is provided at Reference Daily Intake.

Canada

[edit]Health Canada published recommended dietary intakes (DRIs) and tolerable upper intake levels (ULs) for vitamin D.[56]

Australia and New Zealand

[edit]Australia and New Zealand published nutrient reference values including guidelines for dietary vitamin D intake in 2006.[156] About a third of Australians have vitamin D deficiency.[162][163]

European Union

[edit]The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) in 2016[57] reviewed the current evidence, finding the relationship between serum 25(OH)D concentration and musculoskeletal health outcomes is widely variable. They considered that average requirements and population reference intake values for vitamin D cannot be derived and that a serum 25(OH)D concentration of 50 nmol/L was a suitable target value. For all people over the age of 1, including women who are pregnant or lactating, they set an adequate intake of 15 μg/day (600 IU).[57]

On the other hand the EU Commission defined nutrition labelling for foodstuffs as regards recommended daily allowances (RDA) for vitamin D to 5 µg/day (200 IU) as 100%.[164]

The EFSA reviewed safe levels of intake in 2012,[157] setting the tolerable upper limit for adults at 100 μg/day (4000 IU), a similar conclusion as the IOM.

The Swedish National Food Agency recommends a daily intake of 10 μg (400 IU) of vitamin D3 for children and adults up to 75 years, and 20 μg (800 IU) for adults 75 and older.[165]

Non-government organisations in Europe have made their own recommendations. The German Society for Nutrition recommends 20 μg.[166] The European Menopause and Andropause Society recommends postmenopausal women consume 15 μg (600 IU) until age 70, and 20 μg (800 IU) from age 71. This dose should be increased to 100 μg (4,000 IU) in some patients with very low vitamin D status or in case of co-morbid conditions.[167]

Food sources

[edit]Few foods naturally contain vitamin D. Cod liver oil as a dietary supplement contains 450 IU/teaspoon. Fatty fish (but not lean fish such as tuna) are the best natural food sources of vitamin D3. Beef liver, eggs and cheese have modest amounts. Mushrooms provide variable amounts of vitamin D2, as mushrooms can be treated with UV light to greatly increase their content.[45][168] In certain countries, breakfast cereals, dairy milk and plant milk products are fortified. Infant formulas are fortified with 400 to 1000 IU per liter,[2][169] a normal volume for a full-term infant after first month.[59] Cooking only minimally decreases vitamin content.[169]

| Food source[2] | Amount (IU / serving) |

|---|---|

| Trout (rainbow), farmed, cooked, 3 ounces | 645 |

| Salmon (sockeye), cooked, 3 ounces | 570 |

| Mushrooms, exposed to UV light, ½ cup | 366[45] |

| Mushrooms, not exposed to UV light, ½ cup | 7[45] |

| Milk, 2% milkfat, fortified, 1 cup | 120 |

| Plant milks, fortified, 1 cup | 100–144 |

| Ready-to-eat cereal, fortified, 1 serving | 80 |

| Egg, 1 large, scrambled | 44 |

| Liver, beef, cooked, 3 ounces | 42 |

| Cheese, cheddar, 1.5 ounce | 17 |

Fortification

[edit]In the early 1930s, the United States and countries in northern Europe began to fortify milk with vitamin D in an effort to eradicate rickets. This, plus medical advice to expose infants to sunlight, effectively ended the high prevalence of rickets. The proven health benefit of vitamin D led to fortification to many foods, even foods as inappropriate as hot dogs and beer. In the 1950s, due to some highly publicized cases of hypercalcemia and birth defects, vitamin D fortification became regulated, and in some countries discontinued.[34] As of 2024, governments have established mandated or voluntary food fortification programs to combat deficiency in, respectively, 15 and 10 countries.[37] Depending on the country,[37] manufactured foods fortified with either vitamin D2 or D3 may include dairy milk and other dairy foods, fruit juices and fruit juice drinks, meal replacement food bars, soy protein-based beverages, wheat flour or corn meal products, infant formulas, breakfast cereals and 'plant milks',[38][170][24] the last described as beverages made from soy, almond, rice, oats and other plant sources intended as alternatives to dairy milk.[171]

Biosynthesis

[edit]

Synthesis of vitamin D in nature is dependent on the presence of UV radiation and subsequent activation in the liver and in the kidneys. Many animals synthesize vitamin D3 from 7-dehydrocholesterol, and many fungi synthesize vitamin D2 from ergosterol.[45]

Vitamin D3 is produced photochemically from 7-dehydrocholesterol in the skin of most vertebrate animals, including humans.[172] The skin consists of two primary layers: the inner layer called the dermis, and the outer, thinner epidermis. Vitamin D is produced in the keratinocytes of two innermost strata of the epidermis, the stratum basale and stratum spinosum, which also are able to produce calcitriol and express the vitamin D receptor.[173] The 7-dehydrocholesterol reacts with UVB light at wavelengths of 290–315 nm. These wavelengths are present in sunlight, as well as in the light emitted by the UV lamps in tanning beds (which produce ultraviolet primarily in the UVA spectrum, but typically produce 4% to 10% of the total UV emissions as UVB). Exposure to light through windows is insufficient because glass almost completely blocks UVB light.[174] In skin, either permanently in dark skin or temporarily due to tannnng, melanin is located in the stratum basale, where it blocks UVB light and thus inhibits vitamin D synthesis.[47]

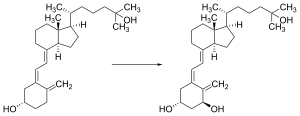

The transformation in the skin that converts 7-dehydrocholesterol to vitamin D3 occurs in two steps. First, 7-dehydrocholesterol is photolyzed by ultraviolet light in a 6-electron conrotatory ring-opening electrocyclic reaction; the product is previtamin D3. Second, previtamin D3 spontaneously isomerizes to vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) via a [1,7]-sigmatropic hydrogen shift. In fungi, the conversion from ergosterol to vitamin D2 follows a similar procedure, forming previtamin D2 by UVB photolysis, which isomerizes to vitamin D2 (ergocalciferol).[5]

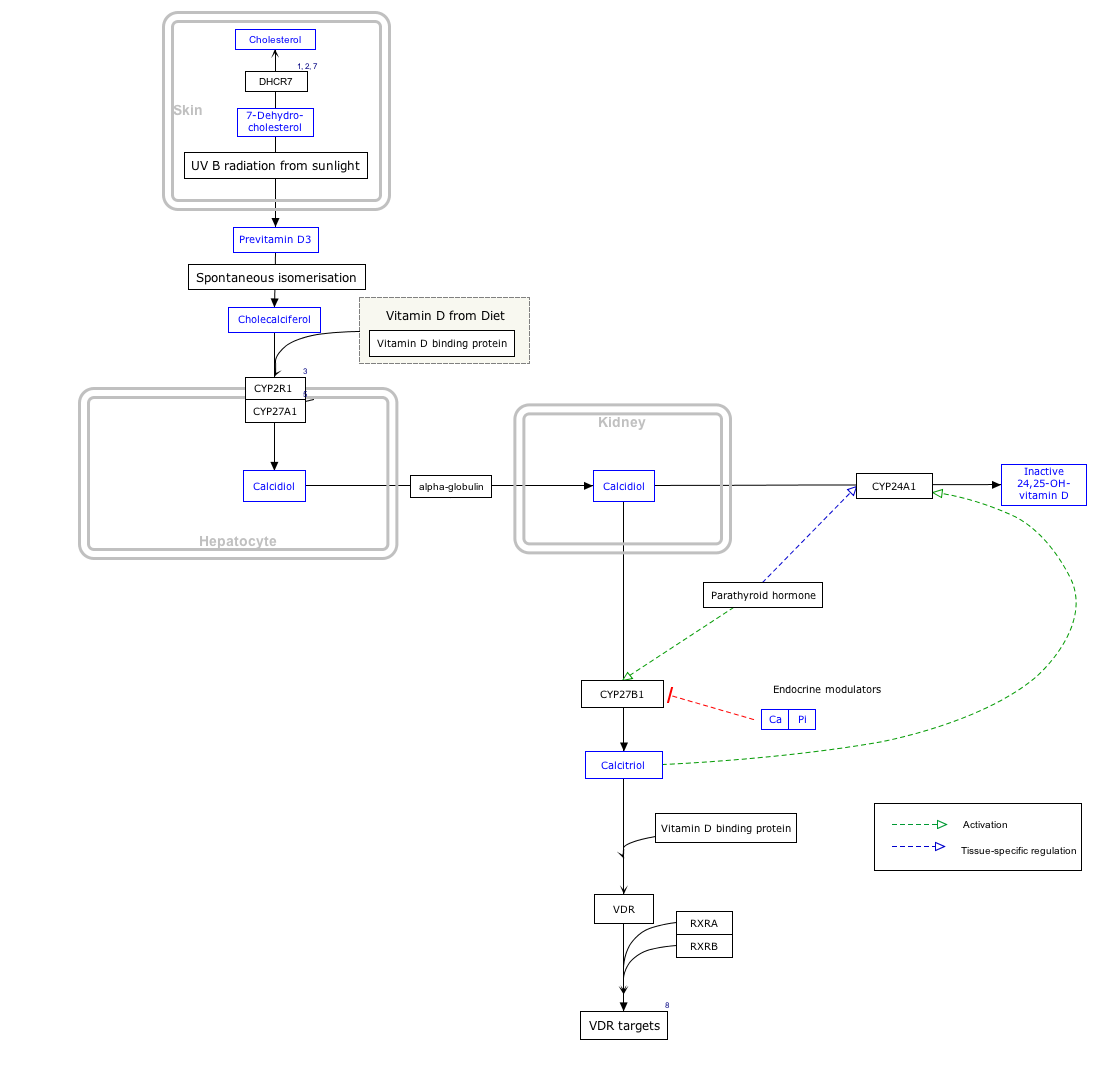

Interactive pathway

[edit]Click on View at bottom to open.

Click on genes, proteins and metabolites below to link to respective articles. [§ 1]

- ^ The interactive pathway map can be edited at WikiPathways: "VitaminDSynthesis_WP1531".

Evolution

[edit]For at least 1.2 billion years, eukaryotes - a classification of life forms that includes single-cell species, fungi, plants and animals, but not bacteria - have been able to synthesize 7-dehydrocholesterol. When this molecule is exposed to UVB light from the sun it absorbs the energy in the process of being conveted to vitamin D. The function was to prevent DNA damage, the vitamin molecule at this time being an end product without function. Present day, phytoplankton in the ocean photosynthesize vitamin D without any calcium management function. Ditto some species of algae, lichen, fungi and plants.[175][176][177] Only circa 500 million years ago, when animals began to leave the oceans for land, did the vitamin molecule take on an hormone function as a promoter of calcium regulation. This function required development of a nuclear vitamin D receptor (VDR) that binds the biologically active vitamin D metabolite 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin (D3), plasma transport proteins and vitamin D metabolizing CYP450 enzymes regulated by calciotropic hormones. The triumvarate of receptor protein, transport and metabolizing enzymes are found only in vertebrates.[178][179][180]

The initial function evolved for control of metabolic genes supporting innate and adaptive immunity. Only later did the VDR system start to functions as an important regulator of calcium supply for a calcified skeleton in land-based vertebrates. From amphibians onward, bone management is biodynamic, with bone functioning as internal calcium reservoir under the control of osteoclasts via the combined action of parathyroid hormone and 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 Thus, the vitamin D story started as inert molecule but gained an essential role for calcium and bone homeostasis in terrestrial animals to cope with the challenge of higher gravity and calcium-poor environment.[178][179][180]

Most herbivores produce vitamin D in response to sunlight. Llamas and alpacas out of their natural high altitude intense solar radiation environments are susceptible to vitamin D deficiency at low altitudes.[181] Interestingly, domestic dogs and cats are practically incapable of vitamin D synthesis due to high activity of 7-dehydrocholesterol reductase, which converts any 7-dehydrocholesterol in the skin to cholesterol before it can be UVB light modified, but instead get vitamin D from diet.[182]

Human evolution

[edit]During the long period between one and three million years ago, hominids, including ancestors of homo sapiens, underwent several evolutionary changes. A long-term climate shift toward drier conditions promoted life-changes from sedentary forest-dwelling with a primarily plant-based diet toward upright walking/running on open terrain and more meat consumption.[183] One consequence of the shift to a culture that included more physically active hunting was a need for evaporative cooling from sweat, which to be functional, meant an evolutionary shift toward less body hair, as evaporation from sweat-wet hair would have cooled the hair but not the skin underneath.[184] A second consequence was darker skin.[183] The early humans who evolved in the regions of the globe near the equator had permanent large quantities of the skin pigment melanin in their skins, resulting in brown/black skin tones. For people with light skin tone, exposure to UV radiation induces synthesis of melanin causing the skin to darken, i.e., sun tanning. Either way, the pigment is able to provide protection by dissipating up to 99.9% of absorbed UV radiation.[47] In this way, melanin protects skin cells from UVA and UVB radiation damage that causes photoaging and the risk of malignant melanoma, a cancer of melanin cells.[185] Melanin also protects against photodegradation of the vitamin folate in skin tissue, and in the eyes, preserves eye health.[183]

The dark-skinned humans who had evolved in Africa populated the rest of the world through migration some 50,000 to 80,000 years ago.[186] Following settlement in northward regions of Asia and Europe which seasonally get less sunlight, the selective pressure for radiation-protective skin tone decreased while a need for efficient vitamin D synthesis in skin increased, resulting in low-melanin, lighter skin tones in the rest of the prehistoric world.[180][179][183] For people with low skin melanin, moderate sun exposure to the face, arms and lower legs several times a week is sufficient.[187] However, for recent cultural changes such as indoor living and working, UV-blocking skin products to reduce the risk of sunburn and emigration of dark-skinned people to countries far from the equator have all contributed to an increased incidence of vitamin D insufficiency and deficiency that need to be addressed by food fortification and vitamin D dietary supplements.[183]

Industrial synthesis

[edit]Vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) is produced industrially by exposing 7-dehydrocholesterol to UVB and UVC light, followed by purification. The 7-dehydrocholesterol is sourced as an extraction from lanolin, a waxy skin secretion in sheep's wool.[188] Vitamin D2 (ergocalciferol) is produced in a similar way using ergosterol from yeast as a starting material.[188][189]

Mechanism of action

[edit]Metabolic activation

[edit]

Vitamin D is carried via the blood to the liver, where it is converted into the prohormone calcifediol. Circulating calcifediol may then be converted into calcitriol – the biologically active form of vitamin D – in the kidneys.[190]

Whether synthesized in the skin or ingested, vitamin D is hydroxylated in the liver at position 25 (upper right of the molecule) to form 25-hydroxycholecalciferol (calcifediol or 25(OH)D).[3] This reaction is catalyzed by the microsomal enzyme vitamin D 25-hydroxylase, the product of the CYP2R1 human gene, and expressed by hepatocytes.[191] Once made, the product is released into the plasma, where it is bound to an α-globulin carrier protein named the vitamin D-binding protein.[192]

Calcifediol is transported to the proximal tubules of the kidneys, where it is hydroxylated at the 1-α position (lower right of the molecule) to form calcitriol (1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol, 1,25(OH)2D).[1] The conversion of calcifediol to calcitriol is catalyzed by the enzyme 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 1-alpha-hydroxylase, which is the product of the CYP27B1 human gene.[1] The activity of CYP27B1 is increased by parathyroid hormone, and also by low calcium or phosphate.[1] Following the final converting step in the kidney, calcitriol is released into the circulation. By binding to vitamin D-binding protein, calcitriol is transported throughout the body, including to the intestine, kidneys, and bones.[13] Calcitriol is the most potent natural ligand of the vitamin D receptor, which mediates most of the physiological actions of vitamin D.[1][190] In addition to the kidneys, calcitriol is also synthesized by certain other cells, including monocyte-macrophages in the immune system. When synthesized by monocyte-macrophages, calcitriol acts locally as a cytokine, modulating body defenses against microbial invaders by stimulating the innate immune system.[190]

Inactivation

[edit]The activity of calcifediol and calcitriol can be reduced by hydroxylation at position 24 by vitamin D3 24-hydroxylase, forming secalciferol and calcitetrol, respectively.[3]

Difference between substrates

[edit]Vitamin D2 (ergocalciferol) and vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) share a similar mechanism of action as outlined above.[3] Metabolites produced by vitamin D2 are named with an er- or ergo- prefix to differentiate them from the D3-based counterparts (sometimes with a chole- prefix).[12]

- Metabolites produced from vitamin D2 tend to bind less well to the vitamin D-binding protein.[3]

- Vitamin D3 can alternatively be hydroxylated to calcifediol by sterol 27-hydroxylase (CYP27A1), but vitamin D2 cannot.[3]

- Ergocalciferol can be directly hydroxylated at position 24 by CYP27A1.[3] This hydroxylation also leads to a greater degree of inactivation: the activity of calcitriol decreases to 60% of original after 24-hydroxylation, whereas ercalcitriol undergoes a 10-fold decrease in activity on conversion to ercalcitetrol.

Intracellular mechanisms

[edit]Calcitriol enters the target cell and binds to the vitamin D receptor in the cytoplasm. This activated receptor enters the nucleus and binds to vitamin D response elements (VDRE) which are specific DNA sequences on genes.[1] Transcription of these genes is stimulated and produces greater levels of the proteins that mediate the effects of vitamin D.[3]

Some reactions of the cell to calcitriol appear to be too fast for the classical VDRE transcription pathway, leading to the discovery of various non-genomic actions of vitamin D. The membrane-bound PDIA3 likely serves as an alternate receptor in this pathway.[193] The classical VDR may still play a role.[194]

History

[edit]

In northern European countries, cod liver oil had a long history of folklore medical uses, including applied to the skin and taken orally as a treatment for rheumatism and gout.[195][196] There were several extraction processes. Fresh livers cut to pieces and suspended on screens over pans of boiling water would drip oil that could be skimmed off the water, yielding a pale oil with a mild fish odor and flavor. For industrial purposes such as a lubricant, cod livers were placed in barrels to rot, with the oil skimmed off over months. The resulting oil was light to dark brown, and exceedingly foul smelling and tasting. In the 1800s, cod liver oil became popular as bottled medicinal products for oral consumption - a teaspoon a day - with both pale and brown oils were used.[195] The trigger for the surge in oral use was the observation made in several European countries in the 1820s that young children fed cod liver oil did not develop rickets.[196] Thus, the concept that a food could prevent a disease predated by 100 years the identification of a substance in the food that was responsible.[196] In northern Europe and the United States, the practice of giving children cod liver oil to prevent rickets persisted well in the 1950s.[195] This overlapped with the fortification of cow's milk with vitamin D, which began in the early 1930s.[34]

Vitamin D was identified and named in 1922.[197] In 1914, American researchers Elmer McCollum and Marguerite Davis had discovered a substance in cod liver oil which later was named "vitamin A".[6] Edward Mellanby, a British researcher, observed that dogs that were fed cod liver oil did not develop rickets, and (wrongly) concluded that vitamin A could prevent the disease. In 1922, McCollum tested modified cod liver oil in which the vitamin A had been destroyed. The modified oil cured the sick dogs, so McCollum concluded the factor in cod liver oil which cured rickets was distinct from vitamin A. He called it vitamin D because it was the fourth vitamin to be named.[6][198][199]

In 1925, it was established that when 7-dehydrocholesterol is irradiated with light, a form of a fat-soluble substance is produced, now known as vitamin D3.[6][7] Adolf Windaus, at the University of Göttingen in Germany, received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1928 "...for the services rendered through his research into the constitution of the sterols and their connection with the vitamins.”[8] Alfred Fabian Hess, his research associate, stated: "Light equals vitamin D."[200] In 1932, Otto Rosenheim and Harold King published a paper putting forward structures for sterols and bile acids,[201] and soon thereafter collaborated with Kenneth Callow and others on isolation and characterization of vitamin D.[202] Windaus further clarified the chemical structure of vitamin D.[203]

In 1969, a specific binding protein for vitamin D called the vitamin D receptor was identified.[204] Shortly thereafter, the conversion of vitamin D to calcifediol and then to calcitriol, the biologically active form, was confirmed.[205] The photosynthesis of vitamin D3 in skin via previtamin D3 and its subsequent metabolism was described in 1980.[206]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Vitamin D". Micronutrient Information Center, Linus Pauling Institute, Oregon State University, Corvallis. 11 February 2021. Archived from the original on 8 April 2015. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Vitamin D: Fact Sheet for Health Professionals". Office of Dietary Supplements, US National Institutes of Health. 12 August 2022. Archived from the original on 9 April 2021. Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Bikle DD (March 2014). "Vitamin D metabolism, mechanism of action, and clinical applications". Chemistry & Biology. 21 (3): 319–329. doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2013.12.016. PMC 3968073. PMID 24529992.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Institute of Medicine (2011). Ross AC, Taylor CL, Yaktine AL, Del Valle HB (eds.). Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. National Academies Press. doi:10.17226/13050. ISBN 978-0-309-16394-1. PMID 21796828. S2CID 58721779. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 17 September 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Giustina A, Bilezikian JP, Adler RA, Banfi G, Bikle DD, Binkley NC, et al. (September 2024). "Consensus Statement on Vitamin D Status Assessment and Supplementation: Whys, Whens, and Hows". Endocrine Reviews. 45 (5): 625–654. doi:10.1210/endrev/bnae009. PMC 11405507. PMID 38676447.

- ^ a b c d Wolf G (June 2004). "The discovery of vitamin D: the contribution of Adolf Windaus". The Journal of Nutrition. 134 (6): 1299–302. doi:10.1093/jn/134.6.1299. PMID 15173387.

- ^ a b Deluca HF (January 2014). "History of the discovery of vitamin D and its active metabolites". BoneKEy Reports. 3: 479. doi:10.1038/bonekey.2013.213. PMC 3899558. PMID 24466410.

- ^ a b "Adolf Windaus – Biography". Nobelprize.org. 25 March 2010. Archived from the original on 24 July 2018. Retrieved 25 March 2010.

- ^ a b Reid IR, Bolland MJ, Grey A (January 2014). "Effects of vitamin D supplements on bone mineral density: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Lancet. 383 (9912): 146–155. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(13)61647-5. PMID 24119980. S2CID 37968189.

- ^ a b c d e Bolland MJ, Grey A, Gamble GD, Reid IR (April 2014). "The effect of vitamin D supplementation on skeletal, vascular, or cancer outcomes: a trial sequential meta-analysis". The Lancet. Diabetes & Endocrinology (Meta-analysis). 2 (4): 307–320. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70212-2. PMID 24703049.

- ^ "The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology: Vitamin D supplementation in adults does not prevent fractures, falls or improve bone mineral density". EurekAlert!. Archived from the original on 24 March 2022. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

The authors conclude that there is therefore little reason to use vitamin D supplements to maintain or improve musculoskeletal health, except for the prevention of rare conditions such as rickets and osteomalacia in high risk groups, which can be caused by vitamin D deficiency after long lack of exposure to sunshine.

- ^ a b "IUPAC-IUB Joint Commission on Biochemical Nomenclature (JCBN): Nomenclature of vitamin D. Recommendations 1981". European Journal of Biochemistry. 124 (2): 223–227. May 1982. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1982.tb06581.x. PMID 7094913.

- ^ a b c Fleet JC, Shapses SA (2020). "Vitamin D". In Marriott BP, Birt DF, Stallings VA, Yates AA (eds.). Present Knowledge in Nutrition (Eleventh ed.). London, United Kingdom: Academic Press (Elsevier). pp. 93–114. ISBN 978-0-323-66162-1.

- ^ Boron WF, Boulpaep EL (29 March 2016). Medical Physiology E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 978-1-4557-3328-6. Archived from the original on 19 March 2023. Retrieved 9 April 2017.

- ^ Bouillon R, Van Cromphaut S, Carmeliet G (February 2003). "Intestinal calcium absorption: Molecular vitamin D mediated mechanisms". Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 88 (2): 332–339. doi:10.1002/jcb.10360. PMID 12520535. S2CID 9853381.

- ^ Holick MF (December 2004). "Sunlight and vitamin D for bone health and prevention of autoimmune diseases, cancers, and cardiovascular disease". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 80 (6 Suppl): 1678S – 1688S. doi:10.1093/ajcn/80.6.1678S. PMID 15585788.

- ^ Watkins RR, Lemonovich TL, Salata RA (May 2015). "An update on the association of vitamin D deficiency with common infectious diseases". Canadian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 93 (5): 363–368. doi:10.1139/cjpp-2014-0352. PMID 25741906.

- ^ Holick MF, Chen TC (April 2008). "Vitamin D deficiency: a worldwide problem with health consequences". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 87 (4): 1080S – 1086S. doi:10.1093/ajcn/87.4.1080S. PMID 18400738.

- ^ a b c Palacios C, Gonzalez L (October 2014). "Is vitamin D deficiency a major global public health problem?". The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 144 (Pt A): 138–145. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2013.11.003. PMC 4018438. PMID 24239505.

- ^ a b Tello M (16 April 2020). "Vitamin D: What's the "right" level?". Harvard Health Publishing. Retrieved 15 December 2024.

- ^ Jiang Z, Pu R, Li N, Chen C, Li J, Dai W, et al. (2023). "High prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in Asia: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 63 (19): 3602–3611. doi:10.1080/10408398.2021.1990850. PMID 34783278.

- ^ Mogire RM, Mutua A, Kimita W, Kamau A, Bejon P, Pettifor JM, et al. (January 2020). "Prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis". The Lancet. Global Health. 8 (1): e134 – e142. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30457-7. PMC 7024961. PMID 31786117.

- ^ Mendes MM, Gomes AP, Araújo MM, Coelho AS, Carvalho KM, Botelho PB (September 2023). "Prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in South America: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Nutrition Reviews. 81 (10): 1290–1309. doi:10.1093/nutrit/nuad010. PMID 36882047.

- ^ a b Spiro A, Buttriss JL (December 2014). "Vitamin D: An overview of vitamin D status and intake in Europe". Nutrition Bulletin. 39 (4): 322–350. doi:10.1111/nbu.12108. PMC 4288313. PMID 25635171.

- ^ a b c d e Amrein K, Scherkl M, Hoffmann M, Neuwersch-Sommeregger S, Köstenberger M, Tmava Berisha A, et al. (November 2020). "Vitamin D deficiency 2.0: an update on the current status worldwide". European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 74 (11): 1498–1513. doi:10.1038/s41430-020-0558-y. PMC 7091696. PMID 31959942.

- ^ a b Harvey NC, Ward KA, Agnusdei D, Binkley N, Biver E, Campusano C, et al. (August 2024). "Optimisation of vitamin D status in global populations". Osteoporosis International. 35 (8): 1313–1322. doi:10.1007/s00198-024-07127-z. hdl:2268/319515. PMID 38836946.

- ^ Cashman KD, Dowling KG, Škrabáková Z, Gonzalez-Gross M, Valtueña J, De Henauw S, et al. (April 2016). "Vitamin D deficiency in Europe: pandemic?". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 103 (4): 1033–1044. doi:10.3945/ajcn.115.120873. PMC 5527850. PMID 26864360.

- ^ Martin CA, Gowda U, Renzaho AM (January 2016). "The prevalence of vitamin D deficiency among dark-skinned populations according to their stage of migration and region of birth: A meta-analysis". Nutrition. 32 (1): 21–32. doi:10.1016/j.nut.2015.07.007. PMID 26643747.

- ^ Lowe NM, Bhojani I (June 2017). "Special considerations for vitamin D in the south Asian population in the UK". Therapeutic Advances in Musculoskeletal Disease. 9 (6): 137–144. doi:10.1177/1759720X17704430. PMC 5466148. PMID 28620422.

- ^ a b Holick MF, Binkley NC, Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Gordon CM, Hanley DA, Heaney RP, et al. (July 2011). "Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 96 (7): 1911–1930. doi:10.1210/jc.2011-0385. PMID 21646368.

- ^ Bischoff-Ferrari HA (2008). "Optimal Serum 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Levels for Multiple Health Outcomes". Sunlight, Vitamin D and Skin Cancer (Review). Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. Vol. 810. Springer. pp. 500–25. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-77574-6_5. ISBN 978-0-387-77573-9. PMID 25207384.

- ^ Dahlquist DT, Dieter BP, Koehle MS (2015). "Plausible ergogenic effects of vitamin D on athletic performance and recovery". Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition (Review). 12: 33. doi:10.1186/s12970-015-0093-8. PMC 4539891. PMID 26288575.

- ^ a b c Freedman BI, Register TC (June 2012). "Effect of race and genetics on vitamin D metabolism, bone and vascular health". Nature Reviews. Nephrology. 8 (8): 459–466. doi:10.1038/nrneph.2012.112. PMC 10032380. PMID 22688752. S2CID 29026212.

- ^ a b c Wacker M, Holick MF (January 2013). "Sunlight and Vitamin D: A global perspective for health". Dermato-Endocrinology. 5 (1): 51–108. doi:10.4161/derm.24494. PMC 3897598. PMID 24494042.

- ^ Hoseinzadeh E, Taha P, Wei C, Godini H, Ashraf GM, Taghavi M, et al. (March 2018). "The impact of air pollutants, UV exposure and geographic location on vitamin D deficiency". Food and Chemical Toxicology. 113: 241–254. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2018.01.052. PMID 29409825.

- ^ Neufingerl N, Eilander A (December 2021). "Nutrient Intake and Status in Adults Consuming Plant-Based Diets Compared to Meat-Eaters: A Systematic Review". Nutrients. 14 (1): 29. doi:10.3390/nu14010029. PMC 8746448. PMID 35010904.

- ^ a b c "Map: Count of Nutrients In Fortification Standards". Global Fortification Data Exchange. 2024. Retrieved 16 December 2024.

- ^ a b "Vitamin D for Milk and Milk Alternatives". Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 15 July 2016. Archived from the original on 22 December 2020. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b c Rooney MR, Harnack L, Michos ED, Ogilvie RP, Sempos CT, Lutsey PL (June 2017). "Trends in Use of High-Dose Vitamin D Supplements Exceeding 1000 or 4000 International Units Daily, 1999-2014". JAMA. 317 (23): 2448–2450. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.4392. PMC 5587346. PMID 28632857.

- ^ a b Mallard SR, Howe AS, Houghton LA (October 2016). "Vitamin D status and weight loss: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized and nonrandomized controlled weight-loss trials". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 104 (4): 1151–1159. doi:10.3945/ajcn.116.136879. PMID 27604772.

- ^ a b Chen L, Chen Y, Yu X, Liang S, Guan Y, Yang J, et al. (July 2024). "Long-term prevalence of vitamin deficiencies after bariatric surgery: a meta-analysis". Langenbeck's Archives of Surgery. 409 (1): 226. doi:10.1007/s00423-024-03422-9. PMID 39030449.

- ^ Saternus R, Vogt T, Reichrath J (2020). "Update: Solar UV Radiation, Vitamin D, and Skin Cancer Surveillance in Organ Transplant Recipients (OTRs)". Sunlight, Vitamin D and Skin Cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol. Vol. 1268. pp. 335–53. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-46227-7_17. ISBN 978-3-030-46226-0. PMID 32918227.

- ^ Tripkovic L, Lambert H, Hart K, Smith CP, Bucca G, Penson S, et al. (June 2012). "Comparison of vitamin D2 and vitamin D3 supplementation in raising serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D status: a systematic review and meta-analysis". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 95 (6): 1357–1364. doi:10.3945/ajcn.111.031070. PMC 3349454. PMID 22552031.

- ^ Alshahrani F, Aljohani N (September 2013). "Vitamin D: deficiency, sufficiency and toxicity". Nutrients. 5 (9): 3605–3616. doi:10.3390/nu5093605. PMC 3798924. PMID 24067388.

- ^ a b c d e Keegan RJ, Lu Z, Bogusz JM, Williams JE, Holick MF (January 2013). "Photobiology of vitamin D in mushrooms and its bioavailability in humans". Dermato-Endocrinology. 5 (1): 165–176. doi:10.4161/derm.23321. PMC 3897585. PMID 24494050.

- ^ Borel P, Caillaud D, Cano NJ (2015). "Vitamin D bioavailability: state of the art" (PDF). Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 55 (9): 1193–1205. doi:10.1080/10408398.2012.688897. PMID 24915331. S2CID 9818323. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 July 2021. Retrieved 27 April 2021.

- ^ a b c Meredith P, Riesz J (February 2004). "Radiative relaxation quantum yields for synthetic eumelanin". Photochemistry and Photobiology. 79 (2): 211–216. arXiv:cond-mat/0312277. doi:10.1111/j.1751-1097.2004.tb00012.x. PMID 15068035. S2CID 222101966.

- ^ Understanding UVA and UVB, archived from the original on 1 May 2012, retrieved 30 April 2012

- ^ a b c d e Ames BN, Grant WB, Willett WC (February 2021). "Does the High Prevalence of Vitamin D Deficiency in African Americans Contribute to Health Disparities?". Nutrients. 13 (2): 499. doi:10.3390/nu13020499. PMC 7913332. PMID 33546262.

- ^ Khalid AT, Moore CG, Hall C, Olabopo F, Rozario NL, Holick MF, et al. (September 2017). "Utility of sun-reactive skin typing and melanin index for discerning vitamin D deficiency". Pediatric Research. 82 (3): 444–451. doi:10.1038/pr.2017.114. PMC 5570640. PMID 28467404.

- ^ a b c O'Connor MY, Thoreson CK, Ramsey NL, Ricks M, Sumner AE (2013). "The uncertain significance of low vitamin D levels in African descent populations: a review of the bone and cardiometabolic literature". Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases. 56 (3): 261–269. doi:10.1016/j.pcad.2013.10.015. PMC 3894250. PMID 24267433.

- ^ Shieh A, Aloia JF (March 2017). "Assessing Vitamin D Status in African Americans and the Influence of Vitamin D on Skeletal Health Parameters". Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics of North America. 46 (1): 135–152. doi:10.1016/j.ecl.2016.09.006. PMID 28131129.

- ^ Powe CE, Evans MK, Wenger J, Zonderman AB, Berg AH, Nalls M, et al. (November 2013). "Vitamin D-binding protein and vitamin D status of black Americans and white Americans". The New England Journal of Medicine. 369 (21): 1991–2000. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1306357. PMC 4030388. PMID 24256378.

- ^ a b c d Durá-Travé T, Gallinas-Victoriano F (July 2023). "Pregnancy, Breastfeeding, and Vitamin D". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 24 (15): 11881. doi:10.3390/ijms241511881. PMC 10418507. PMID 37569256.

- ^ a b c d e f "Vitamins and minerals – Vitamin D". National Health Service. 3 August 2020. Archived from the original on 30 October 2017. Retrieved 15 November 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f "Vitamin D and Calcium: Updated Dietary Reference Intakes". Nutrition and Healthy Eating. Health Canada. 5 December 2008. Archived from the original on 14 June 2017. Retrieved 28 April 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies (NDA) (29 June 2016). "Dietary reference values for vitamin D". EFSA Journal. 14 (10): e04547. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2016.4547. hdl:11380/1228918.

- ^ Kim YJ (May 2013). "Comparison of the serum vitamin D level between breastfed and formula-fed infants: several factors which can affect serum vitamin D concentration". Korean Journal of Pediatrics. 56 (5): 202–204. doi:10.3345/kjp.2013.56.5.202. PMC 3668200. PMID 23741233.

- ^ a b "Feeding Your Baby: The First Year". Cleveland Clinic. 13 September 2023. Retrieved 28 December 2024.

- ^ Dudenkov DV, Yawn BP, Oberhelman SS, Fischer PR, Singh RJ, Cha SS, et al. (May 2015). "Changing Incidence of Serum 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Values Above 50 ng/mL: A 10-Year Population-Based Study". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 90 (5): 577–586. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.02.012. PMC 4437692. PMID 25939935.

- ^ Taylor PN, Davies JS (June 2018). "A review of the growing risk of vitamin D toxicity from inappropriate practice". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 84 (6): 1121–1127. doi:10.1111/bcp.13573. PMC 5980613. PMID 29498758.

- ^ Macdonald HM (February 2013). "Contributions of sunlight and diet to vitamin D status". Calcified Tissue International. 92 (2): 163–176. doi:10.1007/s00223-012-9634-1. PMID 23001438.

- ^ Vitamin D at The Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy Professional Edition

- ^ Brown JE, Isaacs J, Krinke B, Lechtenberg E, Murtaugh M (28 June 2013). Nutrition Through the Life Cycle. Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1-285-82025-5. Archived from the original on 19 March 2023. Retrieved 9 April 2017.

- ^ Insel P, Ross D, Bernstein M, McMahon K (18 March 2015). Discovering Nutrition. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. ISBN 978-1-284-06465-0. Archived from the original on 19 March 2023. Retrieved 9 April 2017.

- ^ Ross AC, Manson JE, Abrams SA, Aloia JF, Brannon PM, Clinton SK, et al. (January 2011). "The 2011 report on dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D from the Institute of Medicine: what clinicians need to know". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 96 (1): 53–58. doi:10.1210/jc.2010-2704. PMC 3046611. PMID 21118827.

- ^ Hathcock JN, Shao A, Vieth R, Heaney R (January 2007). "Risk assessment for vitamin D". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 85 (1): 6–18. doi:10.1093/ajcn/85.1.6. PMID 17209171.

- ^ Vieth R (December 2007). "Vitamin D toxicity, policy, and science". Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 22 (Suppl 2): V64 – V68. doi:10.1359/jbmr.07s221. PMID 18290725. S2CID 24460808.

- ^ Holick MF (March 1995). "Environmental factors that influence the cutaneous production of vitamin D". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 61 (3 Suppl): 638S – 645S. doi:10.1093/ajcn/61.3.638S. PMID 7879731.

- ^ De Paolis E, Scaglione GL, De Bonis M, Minucci A, Capoluongo E (October 2019). "CYP24A1 and SLC34A1 genetic defects associated with idiopathic infantile hypercalcemia: from genotype to phenotype". Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine. 57 (11): 1650–1667. doi:10.1515/cclm-2018-1208. PMID 31188746.

- ^ Tebben PJ, Singh RJ, Kumar R (October 2016). "Vitamin D-Mediated Hypercalcemia: Mechanisms, Diagnosis, and Treatment". Endocrine Reviews. 37 (5): 521–547. doi:10.1210/er.2016-1070. PMC 5045493. PMID 27588937.

- ^ Chung M, Balk EM, Brendel M, Ip S, Lau J, Lee J, et al. (August 2009). "Vitamin D and calcium: a systematic review of health outcomes". Evidence Report/Technology Assessment (183): 1–420. PMC 4781105. PMID 20629479.

- ^ Theodoratou E, Tzoulaki I, Zgaga L, Ioannidis JP (April 2014). "Vitamin D and multiple health outcomes: umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of observational studies and randomised trials". BMJ. 348: g2035. doi:10.1136/bmj.g2035. PMC 3972415. PMID 24690624.

- ^ a b Autier P, Boniol M, Pizot C, Mullie P (January 2014). "Vitamin D status and ill health: a systematic review". The Lancet. Diabetes & Endocrinology. 2 (1): 76–89. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70165-7. PMID 24622671.

- ^ Hussain S, Singh A, Akhtar M, Najmi AK (September 2017). "Vitamin D supplementation for the management of knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials". Rheumatology International. 37 (9): 1489–1498. doi:10.1007/s00296-017-3719-0. PMID 28421358. S2CID 23994681.

- ^ a b Maxmen A (July 2011). "Nutrition advice: the vitamin D-lemma" (PDF). Nature. 475 (7354): 23–25. doi:10.1038/475023a. PMID 21734684. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

- ^ a b Bjelakovic G, Gluud LL, Nikolova D, Whitfield K, Wetterslev J, Simonetti RG, et al. (January 2014). "Vitamin D supplementation for prevention of mortality in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Systematic review). 2014 (1): CD007470. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007470.pub3. PMC 11285307. PMID 24414552.

- ^ Schöttker B, Jorde R, Peasey A, Thorand B, Jansen EH, Groot L, et al. (Consortium on Health Ageing: Network of Cohorts in Europe the United States) (June 2014). "Vitamin D and mortality: meta-analysis of individual participant data from a large consortium of cohort studies from Europe and the United States". BMJ. 348 (jun17 16): g3656. doi:10.1136/bmj.g3656. PMC 4061380. PMID 24938302.

- ^ Tuohimaa P (March 2009). "Vitamin D and aging". The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 114 (1–2): 78–84. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2008.12.020. PMID 19444937. S2CID 40625040.

- ^ Tuohimaa P, Keisala T, Minasyan A, Cachat J, Kalueff A (December 2009). "Vitamin D, nervous system and aging". Psychoneuroendocrinology. 34 (Suppl 1): S278 – S286. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.07.003. PMID 19660871. S2CID 17462970.

- ^ Elidrissy AT (September 2016). "The Return of Congenital Rickets, Are We Missing Occult Cases?". Calcified Tissue International (Review). 99 (3): 227–236. doi:10.1007/s00223-016-0146-2. PMID 27245342. S2CID 14727399.

- ^ Paterson CR, Ayoub D (October 2015). "Congenital rickets due to vitamin D deficiency in the mothers". Clinical Nutrition (Review). 34 (5): 793–798. doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2014.12.006. PMID 25552383.

- ^ Wagner CL, Greer FR (November 2008). "Prevention of rickets and vitamin D deficiency in infants, children, and adolescents". Pediatrics. 122 (5): 1142–1152. doi:10.1542/peds.2008-1862. PMID 18977996. S2CID 342161.

- ^ Lerch C, Meissner T (October 2007). Lerch C (ed.). "Interventions for the prevention of nutritional rickets in term born children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2007 (4): CD006164. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006164.pub2. PMC 8990776. PMID 17943890.